Socrates: Not Guilty

My Take on the Greek Philosopher's Undeserved Death Penalty

The great Greek philosopher, Socrates, was put to death on counts of impiety and corrupting the youth of Athens. While a sound argument can be made that he was guilty of these crimes, there is another, perhaps more rational, contention that Socrates was in fact innocent. Throughout this essay, “piety” shall be roughly defined as a virtue or excellence of living in fulfillment to both gods and humanity. At trial, Socrates is accused of not believing in the gods of Athens, but throughout The Republic, he defends the reputation of the gods and upholds their myths and teachings. He even goes as far as to advocate for the censorship of poets in order to condition the youth to be just; and, in doing so, is not corrupting the youth at all. His very own philosophy was that he could not teach his students what to think, but rather how to think, which is embodied in the quote famously attributed to himself: “I cannot teach anybody anything, I can only make them think” (Socrates).

In the just city that Socrates builds, he calls for the need of a standing army, which he calls the Guardians. A parallel is drawn between the ideal soldier of this army and a “noble puppy” (375a). Both must have an “irresistible and unbeatable spirit” in body and soul. Such a spirit would surely prove beneficial in war, as it would guarantee valor and tenacity in battle. Puppies must be trained and the same holds true for soldiers. In a way, the soldiers will be “bred” for the most desirable traits. There is an adage that old dogs cannot be taught new tricks; thus, Socrates asserts that the city should begin the training of soldiers at a young age. However, the nature of the training presents a controversial issue: censorship.

Socrates believes that some of the Greek poets’ stories should not be told to children because they would lead to an unjust life. Regulating what is and is not taught to youth is a form of manipulation, but there are two sides to this coin. The more obvious case is that what Socrates is advocating is an instance of censorship, which is a dangerous issue, as evidenced rather notably in book burnings during the World War II era. Be that as it may, if one is willing to wipe the grime—that is, the unattractiveness of censorship—from the coin, a substantial silver lining emerges on the flip side. Socrates only aims to censor with good intentions. He cannot rewrite the works of Homer and his companions; the second-best course of action is to prevent the youth from reading those in which the gods commit crimes and practice injustices. This is neither corruption of youth nor impiety. Socrates is doing the exact opposite of what he was eventually charged. He tries to prevent the youth from being corrupted by the evils of injustice. In the following quote, Socrates explains that youth are vulnerable and cannot discern the just from the unjust, and therefore should only be taught stories that exhibit goodness:

A young thing can’t judge what is hidden sense and what is not; but what he takes into opinions at that age has a tendency to become hard to eradicate and unchangeable. Perhaps it’s for this reason that we must do everything to insure that what they hear first, with respect to virtue, be the finest told tales for them to hear. (378d-e)

Even then, by presenting a hand-picked selection of teachings, Socrates never orders his subjects what to believe. It is evident throughout the entirety of Socrates’ dialogue in The Republic, that he kindles introspection. One could imagine having a conversation with Socrates would be frustrating, as he would cause his partner to rethink every response given. Socrates asks obvious and seemingly ridiculous questions so that his students actively contemplate and consider alternate perspectives. In theory and in practice, Socrates could not have been held accountable for corrupting the youth because he never told anyone what to think! The youth could draw whatever conclusions they wanted from the tales they were told, but Socrates wanted to try his best to make sure only the most beneficial tales were told.

Piety is demonstrated in a lifestyle that shows a dutiful respect to gods and humanity. Socrates is a pious individual through his censorship of the poets. He shows nothing but respect for the gods when he claims that the gods are good, perfect, and unchanging. The reason Socrates advocates for censorship is because in many tales, gods commit heinous acts such as homicide, adultery, and theft. Since the gods are a model for youth and the youth cannot judge right from wrong at a ripe age, then the youth could misinterpret such crimes as just. Furthermore, it is possible that the youth might emulate their actions and commit such acts themselves. Doing so would lead to an unjust generation. It is because of this that Socrates’ censorship is not an evil, but rather an amazing good. The true criminal is not Socrates, but the poets. The poets attribute crimes to the gods—which by nature of mythology is morally wrong and analytically impossible—while Socrates is pious in asserting that such stories are “false tales” (377d). Socrates calls the writers of such tales liars; he says that these lies were of an ugly kind. Socrates claims “[w]hat ought to be blamed first and foremost” is “when a man in speech makes a bad representation of what gods and heroes are like” (377d-e). One who condemns someone who commits blasphemy shall not be called impious; it is for this reason that Socrates was grossly mischarged on the count of impiety.

After this examination of Socrates’ actions, it could be confidently ascertained that he was an innocent man in all regards. The hemlock poison kissed much undeserving lips.

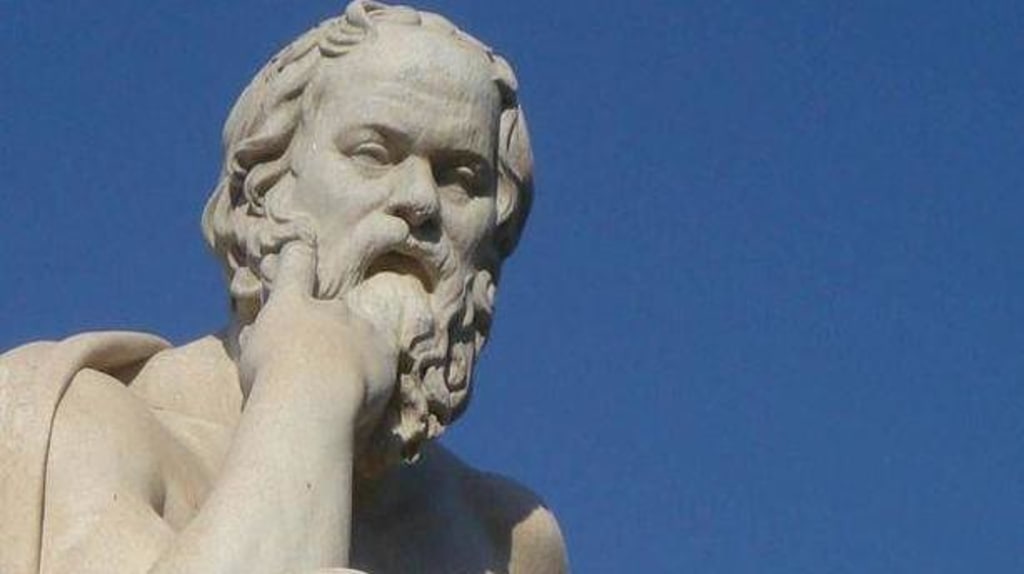

Socrates drinks the hemlock (image source).

Author's note: This article is a personal analysis of the charges brought forth against Socrates. All supporting textual evidence has been obtained through a print version of Plato's Republic, particularly the 2016 version published by Allan Bloom. It can be found here.

About the Creator

Catherine Rose

fierce advocate of using your voice for good

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.