Real Justice for Rape Victims

Nineteenth century thinking and rape myths get in the way of due process.

TRIGGER WARNING: This article discusses the treatment of rape cases in the English justice system, which involves victim-blaming and discussions of victim's sexual histories. It's not very nice, and you may find parts of this piece upsetting.

Everyone knows the 6 percent figure when we discuss the woefully low number of rape convictions in the UK. That’s the proportion of all reported rapes that are convicted. But it’s important that we identify what we actually mean by that. Diagrams like the one below give a better idea (a picture tells 1000 words, etc., etc.), showing us where the other 94 percent disappear from the legal system. More of these assaults are lost without the police getting involved—either victims do not report it, or the police do not record it. It's only 6 percent of the ones we know about.

Source: Liverpool Echo

In addition to those cases that don’t make it past the local police station, many are filtered out between reporting and the courtroom. The criminal courts in the UK err very much on the side of caution when attempting to prosecute any case, whatever the crime. Before a trial is even considered, there are other hurdles that must be passed to determine whether a robust enough case can be brought before a jury. First, the police must decide whether there is enough evidence to charge a suspect. If yes, it is then referred to the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), and they make a further decision based on narrower, more stringent criteria. If the evidence is strong enough for both the police and CPS to pursue the charge to trial, it will then proceed to court. Within the courtroom, the jury is asked to only give a “guilty” verdict if they are sure beyond all reasonable doubt, which is a pretty high bar.

The 6 percent figure sounds particularly bad, but that is the proportion of all reported rapes that are successfully convicted. If we look only at the cases that go to trial, there is actually a good chance of conviction—well, much the same as any other crime tried in court—around 58 percent guilty. The huge rate of attrition is mainly occurring before a trial could even take place.

There are a ton of checks and balances in place to minimise the chances of wrongful convictions. Aside from being an affront to proper justice, wrongful convictions are expensive for the state, and devastating for those directly affected. It costs thousands of pounds to run a criminal trial, so the CPS want to be sure it’s going to be worthwhile doing so—hence the need for robust evidence. It does also mean that many criminals will either walk free or not even see the inside of a courtroom. But that is the price our society has decided to pay for skewing our preference towards avoiding false positives. While the legal system is poor at prosecuting rapes, the court system is not where the problems lie, in terms of the numbers, at least.

Returning to the 6 percent figure, from the time a crime is committed through to a potential trial, rape has a proportionately lower conviction rate. While we have a robust and balanced legal system, the way that rape cases are tried is highly political. The UK also has a lower conviction rate for rape compared to most other European countries. There is a willingness to try to rectify the issue, and it’s important to consider where we should direct resources. It has been recognised by the state that we need to focus on gathering evidence and supporting victims prior to any trial. This resulted in additional resources and special training for police forces, and dedicated teams to work with victims sympathetically, and gather evidence quickly and thoroughly.

Unfortunately, it can be very difficult to gather that evidence. In virtually all rapes, there are no independent witnesses. In many cases, nobody disputes that sex took place, but the issue is that one party disagrees that consent was given—and that itself is very difficult to prove. This is often minimised in popular discourse as “he-said, she-said,” but looking at it objectively, in those cases it really does come down to one person’s word against another’s, and that is rarely going to meet the standard to go to trial. It’s not a matter of anyone being dishonest, changing their mind after the event, or any other excuse—it’s the simple fact that it is so difficult to gather evidence that is strong enough to take to court.

We should also remember that using legal terms like “guilty” and “not guilty” alongside regular speech like “innocent” and “didn’t do it” confuses the matter. This can give an incorrect assessment of what actually happened. If a case doesn’t make it to trial, or a “not guilty” verdict is reached, or a verdict is appealed or a case collapses, that doesn’t mean that no crime happened. It means that the system has worked the way it is designed to. Innocence is not the same thing as a “not guilty” verdict. The standard of proof needed in a criminal court is very high, and the difficulty in bringing a convincing case is down to the nature of the evidence it was possible to gather. But the emotive nature of sex crimes instils in many people a need for certainty, a certainty that we cannot have.

Bad Courtroom Experiences

Another stumbling block on the way to trial is whether victims are comfortable submitting evidence and being questioned in court. This is a hugely traumatic time for many, having to relive the events in front of a room of people who have congregated to determine the credibility of their story. The accuser has already experienced terrible things, and many don’t feel that they will benefit from pursuing justice. The current way that rape victims are treated in court is an impediment to justice. The police and other professionals have recently been instructed to focus on believing victims, i.e. not dismissing them out of hand based on outdated stereotypes and beliefs about rape and the value of women’s testimonies. They have also been tasked with properly supporting women to pursue the matter to trial. These are all positive steps, but have they been effective?

Source: Rape Crisis Scotland

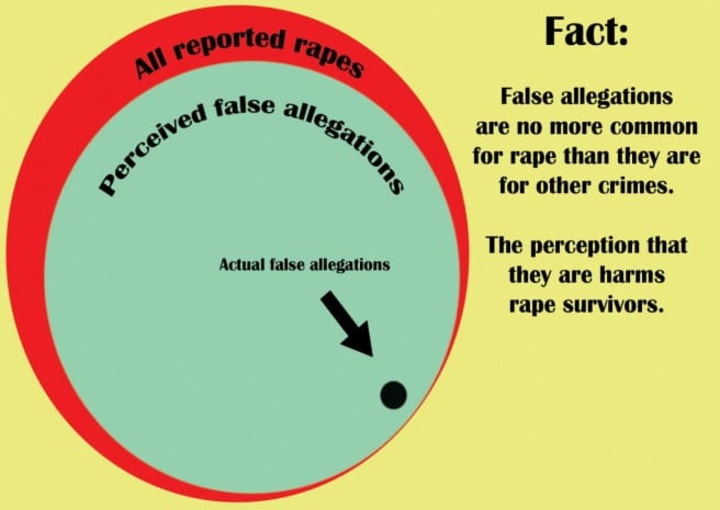

We do need to work towards getting justice for all victims. But we cannot circumvent the proper processes—else we will see more miscarriages of justice. On top of the problems that this poses, there are a load of myths about “false rape allegations” that would just get inflamed by such actions and make the situation even worse. In order to facilitate meaningful change without side-stepping justice, a law was introduced to make it easier for victims to bring cases to court. Section 41 of the Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act 1999 forbids defence barristers from cross-examining accusers about their sexual history or behaviour, unless it is in cases where it was absolutely crucial and relevant. However, recent studies into courtroom practices have shown that the law is not being adhered to, and nothing is being done about it.

Harriet Harman MP QC and Dame Vera Baird QC have petitioned the government for a change in the law, due to the current legislation not protecting victims as intended. They also query the government's use of statistics, given the government data paints a very different picture to the evidence from actual cases. It appears, if we compare the government’s report on the usage of Section 41 with the findings from a review of 550 rape trials by sexual violence consultancy LimeCulture, that the law is being misused in a way that is difficult to record. The government report comments on the small number of cases where a request is submitted under Section 41 to admit certain evidence (of which an even smaller number of requests is granted), and claims this as evidence that the system works as intended. However, the independent report by LimeCulture notes that in cross-examination, defence barristers asked questions that are forbidden without the trial judge’s approval in a huge 75 percent of cases, and nothing was done to challenge or prevent this. It's not possible to record cases where the question wasn't even asked of the judge. This law is not working, and extremely personal and irrelevant evidence is routinely being brought before the courts to cast doubt on the credibility and character of victims.

Why have defence barristers been allowed to continue to interrogate victims on matters that they were told they would not be asked? The law was changed for two reasons:

- To encourage more victims to give evidence at trial, as the cross-examination process had been found to be humiliating and gruelling;

- To eliminate from trial proceedings the myth that “unchaste women are more likely to consent to intercourse and in any event are less worthy of belief.”

We don’t know how many people this has discouraged from going to court, but what we have seen is women being prosecuted for feeling unable to take the witness stand, which is only going to encourage even more women to not report sex crimes against them. We work so hard to make the system more accessible, and then mistakes like this undo those positive measures.

Regarding the second point, that sort of language, and the attitudes attached to it, belong in the 19th century. But recent cases have been reported on because of out-of-dateremarksmadebycertainjudges and barristers. It would seem that it is still a relevant concern in 2018, and so it’s even more important that we do not fuel the concept of sexually-active women being untrustworthy and of loose morals. It could well be that the judge’s ingrained prejudices are the reason why they are not challenging barristers on inappropriate remarks about sexual history.

Some Examples in the Media

I was shocked at Ched Evans’s successful appeal against his rape conviction in 2016, because the new evidence presented to the judge seemed to be exactly the type of thing that the 1999 change in the law sought to prevent: it was testimonies from other lovers stating that the victim had behaved in similar ways to those she is alleged to have behaved (according to Evans, not her) on the night the alleged rape took place. This is only supposed to be permitted in limited circumstances, and it seems odd that this was deemed to comply with those criteria.

womenareboring has created summaries of the original verdict, the change to the law, and the appeal ruling, which you can access in the three links below. Their overview condenses a complex and contentious case into unbiased, plain English.

- Using Evidence of Previous Sexual History in Rape Cases: The Ched Evans case, Part 1

- Using Evidence of Previous Sexual History in Rapes Cases: The Ched Evans case, Part 2

- Using Evidence of Previous Sexual History in Rapes Cases: The Ched Evans case, Part 3

I wouldn’t have thought that saying “fuck me harder” or “go harder” would be particularly unusual or unique phrases to use during lovemaking, but maybe I’m some sort of pervert. While most defendants in rape cases don’t have access to a bottomless pot of money, or the type of expert legal counsel or media attention that someone in Evans’ position would, it worries me that a woman’s sexual idiosyncrasies can be used against her as evidence in court. It says nothing about whether consent was given, and digs up the old myth that if a woman is raped, her behaviour must fulfill certain arbitrary criteria for it to “really” be rape.

Another case in the news is that of Liam Allan, who had been on bail for two years awaiting news from the CPS on whether the case against him would proceed. Much was made in the media of the effect on his life, yet nothing was mentioned about the effects on the accuser. This is one of the recent cases that was dismissed due to the police failing to disclose relevant evidence to the defence team. The evidence that they did not pass on was a series of WhatsApp conversations between defendant, others, and accuser in which she had “pestered him for casual sex,” and described violent sexual fantasies. The trouble with this is that it’s difficult to tell whether this is actually relevant, or if it would serve to use the accuser’s sexual history against them. While she may well have pestered him for sex in the past, that does not mean that on the occasion in question she consented. Or it might relate to that occasion, or it might be relevant in some other way. We don’t know, because the details aren’t available. We also don't know why the police did not pass the information on—although there have been accusations that the police and CPS are so keen to get results that this desire "overrides the duties of the police and the crown." This is a path we must not go down.

It is concerning, however, that a woman’s private social media history could also be used against her should she need to take a rapist to court. And it is difficult to see how evidence of previous sexual contact demonstrates that any future sexual contact must also be consensual. This is one of the most obvious rape myths. Having said that, spousal rape only became a crime in the UK in 1991, so perhaps it is still a confusing notion in the minds of many.

Seeing as the courts seem to revel in scouring through victim's sexual histories, isn't it time we asked about the defendant's background? That is what the Director of Public Prosecutions told prosecutors in August 2017. The hope is that this will shift the notion of blame onto the accused rather than the accuser, and provide context for rapes that have occurred as part of a pattern of abusive behaviour. Like many issues that predominantly affect women, the UK is only just paying attention to domestic abuse and sexual assault, but at least we are doing something now. Making the defendant accountable for their actions, rather than the accuser, will hopefully see that justice is done and will prevent rapists from claiming consent was given when it wasn't.

The next example occurred in Spain, but given the judiciary’s lax attitude to permitted evidence, I see no reason why this couldn’t happen in Britain. A woman alleged an ex-partner raped her, and he was let off because they had previously engaged in BDSM activities. Consent is a huge talking point in the BDSM community, in that whatever activities or fantasies you’re engaging in, you have to be sure that you have it. A case like this one sets a dangerous precedent—consent was allegedly not given, but it was assumed that it could be part of a rape fantasy scene, so it got thrown out of court. Not only is this a misunderstanding of, and a huge insult to, the BDSM community; it’s dangerous for those outside the community too. There are numerous instances of murder and rape where the accused relied on the “kinky sex gone wrong” defence, where there was no consent or even necessarily a history of such activities.

Much has been made of the possibility that fears over being believed, or torn to shreds in court, can put women off from coming forward. This is a huge factor in the 6 percent attrition rate. The overwhelming majority of those rapes that we don’t hear about vanish without a single word being said to anyone in the legal system. But what are we to think, when those in charge of the system continue to habitually disbelieve women and perpetuate stereotypes?

We need to do better.

The law isn’t working, justice is not occurring, and one end of the system tries to help victims while the other punishes them. Perhaps we don’t need to change the law—we just need to actually enforce it. The bias against victims makes a terrible situation worse and discourages people from seeking justice. Over the last decade or so, a lot of work has been done to educate the general public on what “real” rape actually is; yet those who enforce the law still seem to believe that rape is about a woman’s character, or how she lives her personal life. And so we have, in 2018:

- Judges that will not respect a law introduced to protect women from slurs on their character and sexual shame;

- Victim’s sexual history and behaviour openly discussed in court;

- Social media messages used to prove that a victim may have previously had sexual contact with the accused (which is not a surprise, given that around 90 percent of rapes are committed by someone known to the victim);

- The instance of sexual activity being tried as rape being conflated with other sexual encounters, both with the defendant and with others;

- Consensual sex in the past used as an indicator of the accuser’s willingness to engage in sex in future.

It would appear that for each step forward we make in trying to obtain justice, we are pushed two steps back. The legal system is skewed in favour of criminals, simply by virtue of the high attrition rate for many crimes. But the victims of rape vanish from the system at a higher rate, and their journey is far tougher and more personal than for other crimes. The accuser’s integrity and worth is under attack, even though they are the wronged party. When it reaches the courtroom, rape has a similar conviction rate to other crimes. But those victims that do attend court may have to sit through inappropriate questioning that isn't even permitted. Others don't even make it to the courtroom, partly through fear of such humiliating treatment at the hands of defence barristers.

Lots of work is being done with the police, to improve on circumstances that previously let a lot of victims down. But in the courtroom we are still centuries behind. If we encourage and support victims to come forward, and then allow them to be re-victimised in the dock, we are still failing them. Things will improve eventually, but we must swiftly end the present situation of some judges allowing inadmissible questioning, and expressing beliefs that belong in the history books.

The British legal system is often upheld as one of the best and fairest in the world. As well as ensuring that victims are treated fairly and compassionately, we must also stick to the principles of the legal framework. Where vital evidence is not disclosed to the relevant legal teams, it harms accusers as well as the accused. If a trial collapses due to a failing like this, it undermines the security of convictions and the credibility of victims.

Reporting on this problem is a source of conflict for me: on the one hand, it’s important that we talk about barriers to justice, and highlight practices that fail victims. But in doing so, we may contribute to the unwillingness to report sex crimes, and to pursue the matter in court. Knowing what I know about our imperfect system, I could not say what I would do if I was in that awful situation. But I also want other victims to feel comfortable exercising their legal right, and taking back some control from their attacker. Maybe I cannot answer that question until the system is fixed.

About the Creator

Katy Preen

Research scientist, author & artist based in Manchester, UK. Strident feminist, SJW, proudly working-class.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.